I was taught that libraries can be linked one of two ways: statically or dynamically.

Computer people love these two words and use them every time they can. Static and dynamic typing, static and dynamic scoping rules.

In the case of linking, the nomenclature describes whether the resulting binary has depencencies that will still be unresolved when it will be loaded into memory for execution.

For a symbol to be resolved statically, the linker (typically link.exe on Windows and ld on Linux) needs access to the full compiled code, and will hardcode the addresses of procedures and global variables as the operands of the instructions that use them.

For example, when compiling (and linking) this code:

/* foo.c */

extern void foo(void) { /* ... */ }

/* main.c */

extern void foo(void);

int main(void) {

foo();

}

You’ll get an executable that looks (in pseudo-assembly) like this:

foo:

0x01234567 ; body of foo

...

main:

0x0A234567 jump 0x01234567 ; jump to the first instruction of foo

When the processor reaches the jump instruction, it looks at the memory address right next to it and, well… jumps there. It assigns that pointer to the program counter, which makes execution continue from there.

But when the linker doesn’t have access to the full code, and doesn’t know the starting address of foo (as the procedure is defined in a different binary), this step can’t be done. The jump instruction doesn’t know where to jump to until someone finds out where foo is located and writes its address in there.

This is the difference between “static” and “dynamic” linking.

However, the case of dynamic linking still leaves one question unanswered: if it isn’t the linker, who is the one that locates the missing symbol, and when does it fix the pointer?

I’ve heard people subdivide dynamic linking further into implicit dynamic linking and explicit dynamic linking. This reflects the fact that there are, in fact, two possible answers to my question; these two approaches are quite different though, and they allow the programmer to solve different problems. Just saying “dynamic linking” to indicate both of them is quite reductive.

What are these two approaches?

In the first one (implicit), symbols are resolved at load time, by a collaboration between the linker and the operating system’s loader.

The linker creates in the binary a jump table, where each row corresponds to a missing symbol. The usage sites of the symbols in question receive as an operand an index into the jump table at the corresponding row.

main:

0x0A234567 jump 0x0B234567 + 0 ; jump to entry 0 of the jump table

...

jump_table:

0x0B234567 jump ??? ; entry 0 corresponds to foo, the address of which is still unknown

The linker also writes what the binary’s dependencies are (which dynamic libraries contain the missing symbols’ definitions).

When the program is launched, the operating system’s loader takes the executable and all its dependencies; it then looks at the jump table and tries to fill it with the addresses of the corresponding symbol in the libraries.

; Inside the loaded copy of main.exe

main:

0x0A234567 jump 0x0B234567 + 0 ; jump to entry 0 of the jump table

...

jump_table:

0x0B234567 jump 0x0F234567 ; entry 0 corresponds to foo, the address of which

; has been found by the loader

Inside the loaded copy of foo.dll

foo:

0x0F234567 ; body of foo

The implementation details of this method vary from one OS to another, but in general the loader will make sure that no program can run when some of its symbols are still unresolved.

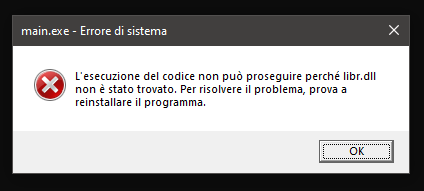

For example, on Windows, trying to run a program without its associate library will bring up this message box:

The code execution cannot proceed because libr.dll was not found. Reinstalling the program may fix this problem.

But what if we want to run a program when some of its symbols are unresolved? What if the programmer wants to have more control over how the linking works, the time at which it happens and the logic behind it?

This is what the last kind of linking (explicit) is for. Windows and Linux both provide a way to do it, though they make it more cumbersome than the other two methods.

By defining foo as a procedure pointer, neither the linker nor the loader will complain about a symbol being unresolved. Procedure pointers are just pointers, after all.

/* foo.c */

extern void foo(void) { /* ... */ }

/* main.c */

typedef void Void_Proc(void);

static Void_Proc *foo;

If we manage to manually assign to foo its correct value, we can then call it as usual:

/* main.c */

int main(void) {

foo = ...; // assign the pointer *somehow*

foo();

}

Fortunately, both Windows and Linux provide ways to figure out what the correct value of foo should be. The exact signatures are of course different, but the idea is the same; first, load the library contents into memory:

/* main.c */

{

// If on Windows:

HANDLE foo_library_handle = LoadLibraryA("foo.dll");

// If on Linux:

void *foo_library_handle = dlopen("foo.so", RTLD_LAZY);

}

From the library handle, get the procedure’s start address:

/* main.c */

{

// If on Windows:

foo = (Void_Proc *) GetProcAddress(foo_library_handle, "foo");

// If on Linux:

foo = (Void_Proc *) dlsym(foo_library_handle, "foo");

}

And you’re done.

You can see how this is quite different than the other flavour of “dynamic linking”, as it allows the program to choose when a library is loaded and linked, and even if the library should be loaded. You can imagine the library names being the result of some computation instead of being static strings like the ones in the example, and you can imagine a program un-linking and re-linking symbols at will at any time.

Here is the full “dynamic explicit” code, (without any error-checking noise):

/* foo.c */

#if OS_WINDOWS

__declspec(dllexport) void foo(void) { /* ... */ }

#elif OS_LINUX

__attribute__ ((visibility ("default"))) void foo(void) { /* ... */ }

#endif

/* main.c */

#if OS_WINDOWS

#include <windows.h>

#elif OS_LINUX

#include <dlfcn.h>

#endif

typedef void Void_Proc(void);

static Void_Proc *foo;

int main(void) {

#if OS_WINDOWS

HANDLE foo_library_handle = LoadLibraryA("foo.dll");

foo = (Void_Proc *) GetProcAddress(foo_library_handle, "foo");

#elif OS_LINUX

void *foo_library_handle = dlopen("foo.so", RTLD_LAZY);

foo = (Void_Proc *) dlsym(foo_library_handle, "foo");

#endif

foo();

}

Note: This post was based on this Allen Webster’s stream. If you want to know more about pros and cons of each kind of dynamic linking, and how runtime linking might be used to one’s advantage, I suggest you go watch that recording. If you want a more structured and comprehensive reference, you can read this page.